Since the evolution of Homo sapiens, our world has been driven by flashes of inspiration, the process we call creativity. But while creativity may appear to be a spontaneous burst of new ideas, it is really the art of deriving the new from the old – the relentless reassembly of information we already possess.

The enduring question with creativity has always been whether the defining factors come from nature or nurture. Everyone can learn to be creative to some degree, but new research has revealed that the extent to which we're born creative may be greater than previously thought.

Two years ago Kenneth Heilman and his team at the Department of Neurology and Neuroscience at Cornell University discovered that the brains of artistically creative individuals have a particular characteristic that may enhance creativity.

The brain is divided into two halves, or hemispheres, that are joined by a bundle of fibres called the corpus callosum. Writers, artists and musicians were found to have a smaller corpus callosum, which may augment their creativity by allowing each side of their brain to develop its own specialisation. The authors suggest that this "benefits the incubation of ideas that are critical for the divergent-thinking component of creativity".

This does not tell the full story, however. Creativity is not only about divergent thinking but also generating endless associations. Recent findings suggest that the secret to this lies in our DNA.

"Creativity is related to the connectivity of large-scale brain networks," says Szabolcs Keri of the National Institute of Psychiatry and Addictions in Budapest. "How brain areas talk to each other is critical when it comes to originality, fluency and flexibility."

In highly creative individuals this connectivity is thought to be especially widespread in the brain, which may be down to genes that play a role in the development of pathways between different areas. These genes reduce inhibition of emotions and memory, meaning that more information reaches the level of consciousness.

In a study published in PLoS ONE earlier this year, researchers from the University of Helsinki assessed people's musical creativity based on their ability to judge pitch and time as well as skills such as composing, improvisation and arranging. They found that the presence of one particular cluster of genes correlated with musical creativity. Crucially, this cluster belongs to a gene family known to be involved in the plasticity of the brain: its ability to reorganise itself by breaking and forming new connections between cells.

The team also observed increased creativity in participants with duplicate DNA strands containing a gene that affects the processing of a key neurotransmitter called serotonin. This finding has been backed up by a newly published neuroimaging study which found that elevating serotonin levels in the brain increases connectivity in one of its most important "hubs" – an area called the posterior cingulate cortex.

The result is particularly interesting because while serotonin is widely known for regulatingsleep, body temperature and libido, the varying levels of this chemical have been implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders such as bipolar depression.

Over the past 40 years, Swedish scientists at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm have been conducting one of the largest population-based studies on individuals with mental illnesses and their siblings. They found that while severe forms of disorders such as schizophrenia tended to be detrimental for cognition and creativity, individuals with bipolar disorder often ended up in professions where creativity was crucial.

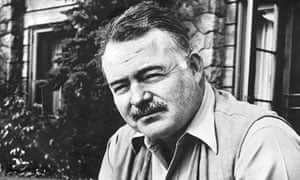

"The finding that bipolar is associated with creativity is not surprising," Keri said. "It is totally in accordance with life histories of famous people like Churchill, Beethoven and Hemingway who have all shown bipolar-like patterns. In bipolar mania, you have an excessive fast and divergent thinking, increased self-esteem, and never-ending energy and motivation, often to create.

"In severe schizophrenia, however, there is a marked impairment of attention and memory, loss of interest, and general slowness. These negative symptoms, absent in typical bipolar patients during 'up' states, have a negative effect on creative output."

But even more intriguingly, the relatives of patients with neuropsychiatric disorders also tended to be more creative. Even though they don't share the illness, they have much in common genetically, suggesting that it is the underlying gene mechanisms, rather than the disorder itself, that is the source of the creative ability.

However, while the discovery of such "creativity genes" indicates that certain people may have a natural propensity for divergent thinking, this does not tell the whole story. A lot depends on how your genes are expressed and this is where the environment can play a defining role.

"We found that many individuals with artistic creativity suffered from severe traumas in life, whether it be psychological or physical abuse, neglect, hostility or rejection," Keri said. "At the biological level, we and several other researchers documented that trauma is associated with functional alteration of the brain, and it also affects the expression of genes that have an impact on brain structure, maybe in the same large-scale networks that participate in creativity."

So, are we born creative or not? While factors such as upbringing play a crucial role in your brain's development, the work done by scientists in Scandinavia, Germany and the US has shown that having the right genetic makeup can make your brain more inclined towards creative thinking. The rest of us have to "learn" to be creative.

The association between creativity and some neuropsychiatric disorders may well help us uncover more of the genes responsible for unlocking our inner creative spirit. But there are many different shades of creativity and the genes that enhance musical ability may not enhance ability in the visual arts. One thing's for certain, we have a lot more to learn about the nature of humans' wonderful creativity.

View all comments >

comments

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion.

This discussion is closed for comments.

We’re doing some maintenance right now. You can still read comments, but please come back later to add your own.

Commenting has been disabled for this account (why?)